As we’ve discussed before (see here and here), one of the primary justifications for the international or extraterritorial prosecution of international crimes is that grave crimes should not go unpunished. The international criminal law tribunals are specifically charged in their founding documents with concentrating on the most serious crimes of international concern or upon high level defendants who are most responsible for the commission of international crimes. At several points within the Statute  of the International Criminal Court (ICC, left), gravity operates as an express limitation on the Court’s jurisdiction and as a guide to the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. And yet, there is little in the Court’s Statute, Elements of Crimes, or other constitutive documents elucidating the quantitative or qualitative contours of this key concept.

of the International Criminal Court (ICC, left), gravity operates as an express limitation on the Court’s jurisdiction and as a guide to the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. And yet, there is little in the Court’s Statute, Elements of Crimes, or other constitutive documents elucidating the quantitative or qualitative contours of this key concept.

An Appeals Chamber of the ICC has recently made public its first ruling on gravity and set forth a blueprint for determining when crimes are sufficiently grave to justify ICC jurisdiction. In so doing, the Appeals Chamber appropriately refocused this inquiry on qualitative rather than quantitative factors, ensuring flexibility in pursuing cases and enhancing the deterrent power of the Court. The ruling is significant not only within the context of the ICC, but also as a source of guidance for other international, hybrid, and national tribunals that must determine which international crimes deserve the exercise of extraordinary jurisdiction. As we’ve discussed before, this very question is of acute relevance before the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, which are now considering a disagreement between that tribunal’s Co-Prosecutors as to whether they should expand their investigations beyond the five high-ranking individuals already in custody.

The concept of gravity permeates the ICC Statute at several key points. According to Article 5(1), the “jurisdiction of the Court shall be limited to the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole.” The prosecutor’s decisions (1) to initiate an investigation into a situation and then (2) to commence a prosecution against a specific individual are premised in part on a determination of a case’s admissibility under Article 17. Article 17(1), in turn, invokes the concept of gravity and provides that a case will be considered inadmissible if it “is not of sufficient gravity to justify further action by the Court.” In addition, pursuant to Article 53, the prosecutor may decline to initiate either an investigation or prosecution where there are “substantial reasons to believe that an investigation would not serve the interests of justice,” taking into account the gravity of the crime and the interests of the victims. Decisions to decline to initiate either an investigation or a prosecution are subject to some oversight by the Pre-Trial Chamber. In the case of a referral from the Security Council or a State Party, the Pre-Trial Chamber can “request the Prosecutor to reconsider [his or her] decision” not to proceed if so requested by the source of the referral. A decision by the prosecutor not to proceed with an investigation or prosecution on the basis of the “interests of justice” (which includes a consideration of the crime’s gravity and the interests of victims) is “effective only if confirmed by the Pre-Trial Chamber.” On the basis of these provisions and prevailing interpretations thereof, gravity concerns are thus relevant before the ICC at two key moments: during the identification of potential situations to investigate and in the choice of particular cases (i.e., crimes or individuals) to investigate and prosecute.

Although crucial investigative decisions are premised upon an objective assessment of gravity, the Statute provides little in the way of concrete guidance about how to undertake this assessment. In his published criteria for the selection of cases and situations, the ICC Prosecutor (left) has indicated that in assessing gravity, he will focus in part on the number of victims of particularly serious crimes, with reference to the scale of the crimes and the degree of systematicity in their commission. At the same time, he indicated that other more qualitative factors would also be relevant, such as whether the crimes are planned, cause “social alarm,” are ongoing or may be repeated, exhibit particular cruelty or reflect other aggravating circumstances, target especially vulnerable victims, are discriminatory in their execution, or involve an abuse of power. In addition, the prosecutor announced that he will consider “the broader impact of the crimes on the community and on regional peace and security, including longer term social, economic, and environmental damage.” By way of example, he noted that the situations currently under consideration in Central and East Africa involved thousands of

assessment. In his published criteria for the selection of cases and situations, the ICC Prosecutor (left) has indicated that in assessing gravity, he will focus in part on the number of victims of particularly serious crimes, with reference to the scale of the crimes and the degree of systematicity in their commission. At the same time, he indicated that other more qualitative factors would also be relevant, such as whether the crimes are planned, cause “social alarm,” are ongoing or may be repeated, exhibit particular cruelty or reflect other aggravating circumstances, target especially vulnerable victims, are discriminatory in their execution, or involve an abuse of power. In addition, the prosecutor announced that he will consider “the broader impact of the crimes on the community and on regional peace and security, including longer term social, economic, and environmental damage.” By way of example, he noted that the situations currently under consideration in Central and East Africa involved thousands of  displacements, killings, abductions, and large-scale sexual violence.

displacements, killings, abductions, and large-scale sexual violence.

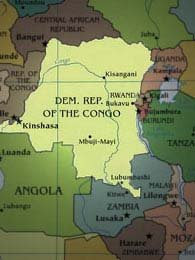

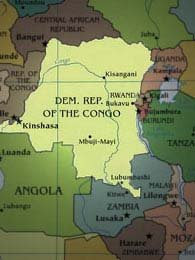

The ICC adjudicated these gravity provisions for the first time in the cases arising out of the ongoing regional war being waged in the Democratic Republic of Congo (map right). The rulings emerged in the context of the prosecutor’s request to the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber for the issuance of arrest warrants against two defendants: Thomas Dyilo Lubanga (Lubanga) and Bosco Ntaganda

Lubanga (Lubanga) and Bosco Ntaganda

Although the Pre-Trial Chamber issued the arrest warrant for Lubanga, it determined that Ntaganda was not a central figure in the decision-making process of his group and lacked any authority over the development or implementation of policies and practices (such as the negotiation of peace agreements). This was notwithstanding the fact that Ntaganda was in a command position over sector commanders and field officers. As such, the case against Ntaganda was deemed inadmissible, and the arrest warrant did not issue.

The Prosecutor appealed this decision, arguing that the Pre-Trial Chamber committed an error of law in defining gravity too narrowly for the purpose of considering the issuance of an arrest warrant against Ntaganda. The Appeals Chamber ruled as a preliminary matter that an admissibility determination was not a pre-requisite to the issuance of an arrest warrant. Turning to the issue of gravity, the Appeals Chamber determined that the Pre-Trial Chamber had erred in its interpretation of gravity in several key respects.

of the International Criminal Court (ICC, left), gravity operates as an express limitation on the Court’s jurisdiction and as a guide to the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. And yet, there is little in the Court’s Statute, Elements of Crimes, or other constitutive documents elucidating the quantitative or qualitative contours of this key concept.

of the International Criminal Court (ICC, left), gravity operates as an express limitation on the Court’s jurisdiction and as a guide to the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. And yet, there is little in the Court’s Statute, Elements of Crimes, or other constitutive documents elucidating the quantitative or qualitative contours of this key concept.The concept of gravity permeates the ICC Statute at several key points. According to Article 5(1), the “jurisdiction of the Court shall be limited to the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole.” The prosecutor’s decisions (1) to initiate an investigation into a situation and then (2) to commence a prosecution against a specific individual are premised in part on a determination of a case’s admissibility under Article 17. Article 17(1), in turn, invokes the concept of gravity and provides that a case will be considered inadmissible if it “is not of sufficient gravity to justify further action by the Court.” In addition, pursuant to Article 53, the prosecutor may decline to initiate either an investigation or prosecution where there are “substantial reasons to believe that an investigation would not serve the interests of justice,” taking into account the gravity of the crime and the interests of the victims. Decisions to decline to initiate either an investigation or a prosecution are subject to some oversight by the Pre-Trial Chamber. In the case of a referral from the Security Council or a State Party, the Pre-Trial Chamber can “request the Prosecutor to reconsider [his or her] decision” not to proceed if so requested by the source of the referral. A decision by the prosecutor not to proceed with an investigation or prosecution on the basis of the “interests of justice” (which includes a consideration of the crime’s gravity and the interests of victims) is “effective only if confirmed by the Pre-Trial Chamber.” On the basis of these provisions and prevailing interpretations thereof, gravity concerns are thus relevant before the ICC at two key moments: during the identification of potential situations to investigate and in the choice of particular cases (i.e., crimes or individuals) to investigate and prosecute.

Although crucial investigative decisions are premised upon an objective assessment of gravity, the Statute provides little in the way of concrete guidance about how to undertake this

assessment. In his published criteria for the selection of cases and situations, the ICC Prosecutor (left) has indicated that in assessing gravity, he will focus in part on the number of victims of particularly serious crimes, with reference to the scale of the crimes and the degree of systematicity in their commission. At the same time, he indicated that other more qualitative factors would also be relevant, such as whether the crimes are planned, cause “social alarm,” are ongoing or may be repeated, exhibit particular cruelty or reflect other aggravating circumstances, target especially vulnerable victims, are discriminatory in their execution, or involve an abuse of power. In addition, the prosecutor announced that he will consider “the broader impact of the crimes on the community and on regional peace and security, including longer term social, economic, and environmental damage.” By way of example, he noted that the situations currently under consideration in Central and East Africa involved thousands of

assessment. In his published criteria for the selection of cases and situations, the ICC Prosecutor (left) has indicated that in assessing gravity, he will focus in part on the number of victims of particularly serious crimes, with reference to the scale of the crimes and the degree of systematicity in their commission. At the same time, he indicated that other more qualitative factors would also be relevant, such as whether the crimes are planned, cause “social alarm,” are ongoing or may be repeated, exhibit particular cruelty or reflect other aggravating circumstances, target especially vulnerable victims, are discriminatory in their execution, or involve an abuse of power. In addition, the prosecutor announced that he will consider “the broader impact of the crimes on the community and on regional peace and security, including longer term social, economic, and environmental damage.” By way of example, he noted that the situations currently under consideration in Central and East Africa involved thousands of  displacements, killings, abductions, and large-scale sexual violence.

displacements, killings, abductions, and large-scale sexual violence.The ICC adjudicated these gravity provisions for the first time in the cases arising out of the ongoing regional war being waged in the Democratic Republic of Congo (map right). The rulings emerged in the context of the prosecutor’s request to the ICC’s Pre-Trial Chamber for the issuance of arrest warrants against two defendants: Thomas Dyilo

Lubanga (Lubanga) and Bosco Ntaganda

Lubanga (Lubanga) and Bosco Ntaganda (left)pursuant to Rule 58(1) of the ICC Statute. In this matter of first impression, the Pre-Trial Chamber determined that it had to confirm the admissibility of the case prior to issuing any arrest warrant. In so doing, the Pre-Trial Chamber looked to several factors.

- First, the Trial Chamber considered the existence of systematic or large-scale crimes.

- Second, Pre-Trial Chamber indicated that it would look to the “social alarm” caused within the international community by the relevant conduct.

- Third, the Pre-Trial Chamber indicated that it would consider the position of the accused and whether he or she fell within the category of the most senior leaders engaged in the situation under investigation, taking into account the role of the suspect in the state or organization implicated in the abuses. The Chamber reasoned that such an interpretation would maximize the deterrent effect of the Court by focusing on those individuals most capable of preventing the commission of international crimes.

The Prosecutor appealed this decision, arguing that the Pre-Trial Chamber committed an error of law in defining gravity too narrowly for the purpose of considering the issuance of an arrest warrant against Ntaganda. The Appeals Chamber ruled as a preliminary matter that an admissibility determination was not a pre-requisite to the issuance of an arrest warrant. Turning to the issue of gravity, the Appeals Chamber determined that the Pre-Trial Chamber had erred in its interpretation of gravity in several key respects.

- First, it noted that imposing requirements of systematicity or large-scale action contradicted the guiding threshold language of Article 8(1) governing war crimes, which provides for jurisdiction only “in particular” when war crimes are committed “as part of a plan or policy or as part of a large-scale commission of such crimes” and duplicated aspects of the definition of crimes against humanity requiring a showing that the charge acts were part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population.

- The Appeals Chamber also took issue with the concept of “social alarm,” which it noted depends on “subjective and contingent reactions” to crimes “rather than upon their objective gravity.”

Finally, the Appeals Chamber noted that the deterrent effect of the Court will be maximized where all categories of perpetrator may be brought before the Court. It also noted that “individuals who are not at the very top of an organization may still carry considerable influence and commit, or generate the widespread commission of, very serious crimes.”